Six Texts

by Gabriel Blackwell

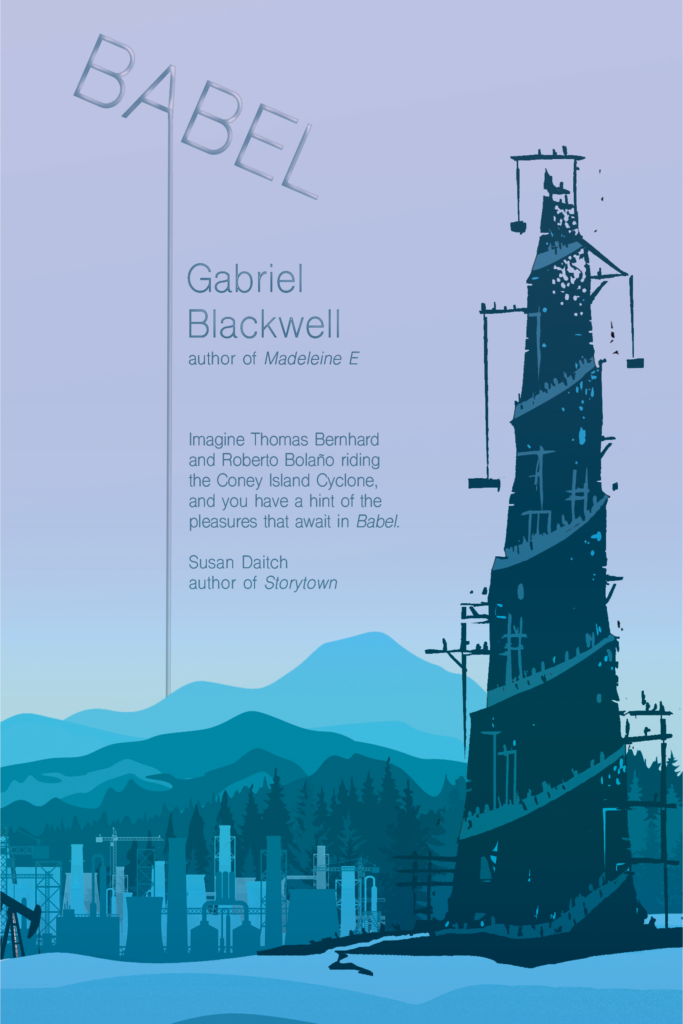

New microfictions by Gabriel Blackwell, author of Babel,

published exclusively online.

Paperback: £9.99

ePub: £3.99

Middle Age

What he’d had, he said, was more in the way of a recognition, not, he said, a revelation. This distinction was, it seemed, important to him. The recognition was that, at forty, he’d expended any potential he’d once had, but he wasn’t in any imminent danger of dying. Was that what was meant by middle age? he asked. It was clear he was thinking something he wasn’t saying. He’d been very nice to her lately. Usually, when his behavior changed for the better, it was because he wanted her to change her behavior in some way — the changes, for him, were rarely lasting. She would have wondered what all this was meant to get her to do differently if only she hadn’t been exhausted by it all.

The Five Ws

A woman from Orlando, they say, forty-two years old, mother to a young son, or so the rumor goes, ex-wife to a man who lived only minutes away from the apartment she shared with her longtime boyfriend, both a complainant and an alleged perpetrator in a 2018 domestic assault — she claimed the boyfriend had pulled her upstairs by her hair and kicked her in the eye; her boyfriend claimed she had strangled him until he almost passed out and he kicked her only to prevent her from killing him; charges in both cases were ultimately dropped — a woman whose Facebook page reveals that her favorite quote is “Anything worth doing, is worth doing well,” which, comma aside, is a paraphrase of something Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield once wrote (a man who was largely responsible for Britain adopting the Gregorian Calendar, less a thing “done well” than a thing done somewhat better than what had come before), a woman who has been charged with second-degree murder. She has been charged because, police say, her statements have been inconsistent following her call to 911 after reportedly finding her boyfriend still zipped in the suitcase, suffocated, bruised, with cuts on his cheek and on his back and no longer alive, calling her ex-husband, informing both the ex-husband and then, later, the police, that the last thing she remembered, before falling asleep, was that she and her boyfriend were playing a game, hide-and-go-seek, and they had both thought it would be funny if he hid in the suitcase — they had been drinking — and that, when she left him, he had two fingers sticking out from the zippered enclosure, and so she felt sure he would be able to get out of the suitcase if he needed to, and that she had, at that particular moment, needed to lay down, and so she had gone to bed, and left the boyfriend in the suitcase, on the floor, in the living room. All of this is the day after, though, the day after she woke up a little before noon, realized she hadn’t heard her boyfriend moving around in a while — she told police she thought he was on the computer — checked the suitcase in the living room, called her ex-husband, called 911, made her statement, gave police permission to search her phone, watched with police the video of herself saying “This is what I feel like when you cheat on me” in response to her boyfriend’s muffled “I can’t breathe, seriously” coming from inside the suitcase, watched with police the video of the suitcase, now in a different place in the apartment but still, clearly, with her boyfriend inside, now not moving. This was in the United States, of course, in Florida, in a suburb of Orlando, which is to say very near the self-proclaimed “Happiest Place on Earth.” Why had she done any of this? Honestly, it’s a good question.

Successful

A successful CPA would never do such a thing, the man’s attorneys argued, so clearly he hadn’t been in his right mind when he’d held the gun to his own daughter’s head with his ex-wife on speakerphone.

Try Again

The State Attorney reminds reporters that children who are victims of violence are often voiceless. This is how she phrases things: We talk about children being voiceless, she says. She says this because the child was voiceless, or, really, more to the point, nonverbal. The boy was autistic, age nine, with a father who loved him and a mother who was, according to the family’s attorney, an excellent mother, just an excellent person. This excellent mother pushed the boy into one of Miami’s canals, knowing that he could not swim. He was rescued by a resident of the neighborhood who heard yelling — evidence, no-one says, that the boy was not after all voiceless. Because the boy had definitely not, however, acquired language, he could not tell his rescuer that it had been his mother who pushed him in. He was returned to his mother, waiting nearby. How odd to be awakened in the night by yelling, dive into the water of a South Florida canal, drag a drowning boy to shore, return him to his mother, get whatever fitful sleep one can after such a thing has happened, and then to read, the next morning, on the internet, that the woman one has turned the boy over to — who was, after all, the boy’s excellent mother — drove him to a golf course not so far away and pushed him into the water there, where, this morning, his body has been found. Possibly, instead, it is on the morning news, an interview with the excellent mother in which she claims it had been two black men who took her cellphone, tablet, and son — the ordering of a list, we are told, reveals one’s priorities — but then the police say, no, there is video footage of her pushing her boy into the first canal, and anyway, this woman on the news is the woman you turned the boy over to, and it is unclear whether you ought to feel guilt, even though of course you feel guilt, you fight with yourself over whether this guilt ought to linger, and it lingers, and it is clear, in that uncertain moment, only that this woman is persistent.

Church Camp

The woman police say has murdered her best friend and kidnapped her best friend’s infant daughter once told her (now ex-) boyfriend — the purported father of her apparently non-existent child — that she had given birth to their child on a weekend at the beach, and, according to the boyfriend’s affidavit, “the child is in the house.” There are, of course, more horrifying parts of the story, like the duffel bag this woman used to move her best friend’s body from the apartment to the trunk of her car, like the discovery of that body in the trunk, like the grief the best friend’s fiancé must feel, or the chaos the child has been born into, but it is this that occupies my thoughts: the woman’s boyfriend reported the woman after seeing a missing persons poster with a picture of the best friend and her child, telling the investigator, again, according to the affidavit, “that’s the baby at my house.” I mean that it is the desperation and fear that at some level we all must feel that this man’s actions and words demonstrate, staying with a woman he clearly did not believe even after she’d returned from a weekend away from home with a child he did not believe was his — or hers — listening, night after night, to her obvious lies about the child, watching her care for the child, perhaps even himself caring for the child as though it was his own even while doubting everything about what his girlfriend was telling him, even after, under the most generous possible reading of her actions and with an incredible amount of credulity, one accepted her claims, she had, monstrously, given birth to his child without even informing him — no phone call, no text, nothing — until she had returned home with the child, only then telling him “the child” — his child — “is in the house.” It is said that the woman met her so-called best friend at church camp.

Victors

The newspaper whose reporters the president banned from covering his rallies reports that a newspaper — another newspaper, one with a much smaller circulation, published in a small town in a Midwestern state — has published an obituary reading, in part, “She abandoned her children, Gina and Jay who were then raised by her parents […] She passed away on May 31, 2018 and will now face judgment. She will not be missed by Gina and Jay, and they understand that this world is a better place without her.” The article gives examples of other, similar obituaries, one from Nevada: “She is survived by her 6 of 8 children whom she spent her lifetime torturing in every way possible […] Everyone she met, adult or child was tortured by her cruelty and exposure to violence, criminal activity, vulgarity, and hatred of the gentle or kind human spirit”; and one from Texas: “Leslie’s hobbies included being abusive to his family, expediting trips to heaven for the beloved family pets and fishing […] With Leslie’s passing he will be missed only for what he never did; being a loving husband, father and good friend.” The article does not mention an earlier example, from California: “Dolores had no hobbies, made no contribution to society and rarely shared a kind word or deed in her life. I speak for the majority of her family when I say her presence will not be missed by many, very few tears will be shed and there will be no lamenting over her passing.” The paper that published this notice, believing the obituary to be a hoax, demanded to see the death certificate before going to print. One can imagine the satisfaction with which the obituary’s author produced the document.

About the Author

Gabriel Blackwell is the author of Madeleine E. (Outpost19, 2016), The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised-Men: The Last Letter of H. P. Lovecraft (CCM, 2013), Critique of Pure Reason (Noemi, 2013), and Shadow Man: A Biography of Lewis Miles Archer (CCM, 2012).