The Proof-Reader

by Nicholas John Turner

This text is excerpted from Nicholas John Turner’s

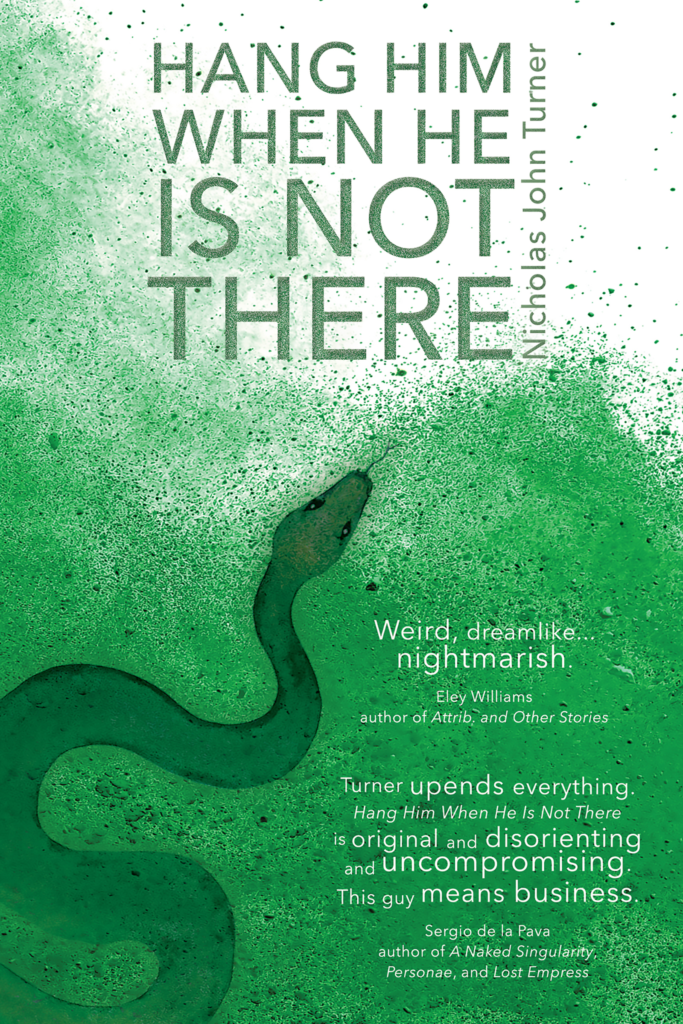

Hang Him When He Is Not There, available now from Splice.

Paperback: £9.99

ePub: £3.99

The tired Queenslander where my mother lived, and in which I had grown up (with, and then without, a father) was too big for her now and she had students and migrants living in the rooms. The veranda was dry, raw and splintery, scattered with empty bottles and newspapers. Dead palm fronds leaned against the balustrades, brittle and bowed, hooked by their sheathes among and over towels and clothes. I had intended to go inside, but realised (and this, after five years, was a revelation) that I didn’t need to, because just by imagining (and by holding my phone—which was ringing over and over now—fast to myself) I could move through that scene that never changed. In the living room, the TV sat on the floor. The bowl of a stilted cot (once my own) was crushed like an egg and laid on its side against a wall, ragged cane at the fractures of its two broken legs. The couches didn’t match and were torn, spilling foam. Indian and African rugs were pinned across windows and doorways, scattered across the floor and bunched in corners. There were no photos. A small table bore sagging candles and the table was fused to the floorboards by wax of many colours, generally blackened. The smell was foreign and putrid. Around a thin wall my mother sits (she, alone, is always in the present—not a memory but a fixture) in the kitchen at a laminated table with thin metal tube legs. She is hunched over some loose, printed pages. I wait, unannounced, at the doorway, and observe her in her ever-present. Her starchy, grey-black hair is tied up in a bun and the loose hairs make a kind of aureole that is lit up by the window behind her. She is a horror of obesity, balancing even as she sits, knees splayed, the shapeless dress of an Islander woman draped over her Danish flesh. Her feet, one bridge atop the other, and bare beneath the table; these are two strange, arced masses. Her ears, alone, are small and elegant. She raises her head first, and then her smudged pupils lift up to illustrate the small square glasses whose chain droops across her shoulders. It is impatience that always greets me, though I might have been missing, or standing right there, forever. My work until then may be described simply, or else in great and ultimately suggestive detail; I was indeed a proof-reader. But even within that specialisation I was a specialist, capable of living for hours, days, weeks or even months among the fine, structural details of a text without once concerning myself with its ultimate relevance or value or meaning. To be clear, I was not and am not an expert in the English language, insofar as I could not have put names to or explained in much detail the grammatical justifications for my work. And nor am I a gifted speller (though these days a computer can manage that). I simply moved from one word to the next, and occasionally back and forth within phrases, or sentences, or paragraphs, or else chapters or entire books, changing this or that word or punctuation or ordering of things, until I felt that a kind of equilibrium had been reached, or else (and this is only to best describe my experience) until I felt as though I could stretch out the whole text in one long line and hold it up to a light to be assured of its straightness, like a pool cue. I went by feel: that is as good as I can do to explain it. A finished text, to me, was a feeling of content or justice, like the end of an itch or an illness, or the trueness of a plane. I had studied to be a journalist, but as a student I had solicited my editorial gifts in an effort to secure the friendships that had always eluded me. As the demand for my services grew beyond the university campus, so did my solitude. In my usefulness I became repulsive. I soon learned that to be so specialised, so precious, and so highly in demand is to become the lowest form of life—an enzyme in the gut. I had always intended to return to journalism, to join my employers as peers, but the more important I became to them, the further I felt from being one of them. And it did not help my cause that those who engaged me were highly secretive about it (to the point of having me sign non-disclosure agreements), and that my reputation spread amongst certain connected worlds like a dangerous rumour. Politicians, noted academics, commentators and critics found their way to my tiny apartment, always by telephone or post. I became used to the idea of money in envelopes. In short, I was passed around the intellectual, political and cultural elite of Australia like a terrible secret. My explicit refusal to work with novelists and poets did nothing to deter their efforts to engage me. I am thinking of one in particular, who (though his face was covered by a handkerchief, so that I’ll never be able to say for sure) having sent me numerous drafts in the mail, which I had dutifully returned, grabbed me by the sleeve one day and pulled me into a little grass area beside the train station near my building. Though he was quite old at the time, he was surprisingly much stronger than I was and had no trouble pinning me to a concrete embankment. His bald head and tired black eyes (eyes that were like looking down the tubes of old socks) were unmistakable, though I admit that neither of us took our hands away from our faces. He thrust a manila folder into my hand before swearing at me and running away. It was a collection of stories, some of them mythical, set in Brisbane, Launceston, and towns in Greece. I read them for pleasure, but ultimately returned them unmarked.

About the Author

Nicholas John Turner is a writer from Brisbane, Australia. Hang Him When He Is Not There is his first novel.